The Hero's Journey is a Jammed Door

It's a myth that's appropriate for a very particular stage of life

I'm going to piss off a lot of people who half-read Joseph Campbell here: the Hero's Journey is not the only story structure.

It's only a monomyth in the way that a particular god is monotheistic — not by being the only one around, but by denying or brushing off all the other ones.

The Hero's Journey is, however, a myth with special significance for our age. There's a reason we're so obsessed with it. It’s not for nothing that this exact story structure is consulted for almost every movie, TV series, novel, and video game.

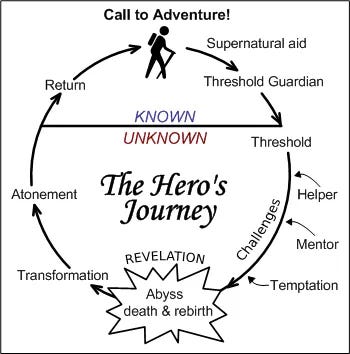

To understand the implications of these two facts (that the hero's journey is not the only myth, and that it is a significant myth for our age), we'll have to look more closely at the myth itself. Or more precisely, we'll have to back away from it to get a better view.

The Hero's Pattern

The explicit use of Campbell's framework – and the ensuing monomythmania – is often traced back to Star Wars, the tale of a young man who leaves home and finds out that there's more to him than he ever knew; he's a Jedi knight!

A more recent example is the story of Harry Potter, a young man who leaves home and finds out there's more to him than he ever knew; he's a wizard!

We find an older example of the structure in The Lord of the Rings, about a young (by hobbit standards) man who leaves home and finds out there's more to him than he ever knew; he saved the world!

And of course a classic example in The Wizard of Oz, about a young woman who leaves home and finds out there's more to her than she ever knew; she killed a witch and unmasked a fake wizard!

I could go on, but the point of the Hero's Journey is coming into focus: it's a myth that's appropriate for a very particular stage of life — it forms a threshold between what we can roughly call adolescence and adulthood. An adolescent leaves normal day-to-day life, meets new friends, faces challenges, discovers that there's more to them (and more to life) than they'd previously thought, learns to make sacrifices and compromises, and then returns to take a new role in the world they come from. They return as a new person, able and willing to do things they couldn't before; able to be someone they couldn't be before.

This isn't an all-purpose story. It's a pattern that enacts a very specific life transition, preparing us for the opportunities and sacrifices of this new stage of life.

This pattern of leaving home, finding out who you are and what you're capable of, then coming back to be what you couldn't be before — it's been press-ganged into acting as the structure for many other kinds of stories, but it's not actually native to or appropriate for them. A story about deepening into your current place in the community doesn't actually fit the Hero's Journey. A story about mentoring youths who are going on their own journeys doesn't actually fit the structure either. A dozen, a hundred other types of stories and patterns from life are not native to this structure — but Hollywood and writers' workshops keep re-shaping them to fit anyways.

There's a good reason for this compulsive tic, though not a popular one to talk about. It is fairly obvious though, if we ask the question directly: why would someone obsessively re-enact, over and over again, the passage from adolescence to adulthood?

The Path of the Soul

There are a lot of ways people chart human development, one of the most compelling being Bill Plotkin's "Soul-Centric Model of Human Development," which manages to express some deep truths about human potential without descending immediately into hierarchical status games. His explanations are always clear-headed and compassionate, and while other models lend themselves very easily to condescension and ego trips, Plotkin shows a deft hand for avoiding those traps.

There's a lot happening in that circle, but for our purposes (and for Plotkin's, mostly) the focus is firmly at 9 o'clock, the line between "Late Adolescence" and "Early Adulthood." The line separating adolescence from adulthood, what Plotkin calls "Soul Initiation," is the native home of the pattern we call The Hero's Journey.

It's relevant — critical, maybe — to note that according to Plotkin, a vanishingly small minority of modern people ever make it to Early Adulthood. Almost no one makes it through soul initiation. The Hero's Journey stands before us, uncompleted.

Other developmental frameworks come to similar conclusions. Robert Kegan, for example, has noted that only a minority of adults surpass stage 3 of his framework, what he calls “Socialized Mind.” This is stage 3 out of 5, in his system, and a stage that most tend to arrive at in their late teens or early 20s. Which is to say, it agrees with Plotkin’s assessment both in saying most of us get stuck halfway, and in zooming in on the approximate age and values we get stuck on. Furthermore, Kegan and Plotkin are far from the only people in the field to come to similar conclusions. It shows up again and again in developmental psychology.

You can react to this revelation in a handful of ways.

A common one is indignation, "what do you mean I haven't crossed into adulthood? I'm 45, I pay my bills, I take care of my kids! Are you saying I'm childish?"

Another one might be dismissal, "Fine, adults are almost extinct according to this definition of adulthood. Why should I care about this particular definition?"

Another important reaction — one you might either suppress or revel in — is recognition.

I can't count the number of times I've heard people say about their workplace, their churches and sanghas, the organizations and friend groups they're a part of, "it's just like high school, all the cliques and fashions and messy feelings thrown around." You only need to turn to the news of the week to watch world leaders, senators, CEOs and billionaires acting out middle school dramas on a grand scale. Check out the advertisements in your neighborhood, at the theater, on your computer — the general youth-obsession, sex-obsession, and identity-obsession take on a very specific texture once you look at them as appeals to a culture stuck between adolescence and adulthood.

Within this frame, the obsessive repetition of the Hero's Journey makes a very specific kind of sense.

A Stuckness Theory of Story Structure

In general, when people compulsively repeat a certain behavior, it's because there's something there they need but aren't getting. You might compulsively eat because you need comfort and aren't getting it anywhere else. You might compulsively over-share because you need acceptance or absolution and aren't getting it anywhere else.

You might compulsively return to stories of reaching adulthood because you need growth and aren't getting it anywhere else.

When these needs and reactions are chronic, continuing over years, decades, lifetimes, it's usually because something inside of you got stuck. There was some stage in your life where a basic need wasn't getting met, and the part of you that couldn't move forward without those needs being met... didn't move forward. In the same way a tree can't grow without sunlight, something inside you couldn't develop without some basic need being fulfilled. There’s a bottleneck some part of you got stuck in.

This kind of stuckness isn't uncommon, and in more extreme cases it becomes a kind of trauma. Peter Levine explains this aspect of trauma on the psycho-biological level:

Trauma is a highly activated incomplete biological response to threat, frozen in time. For example, when we prepare to fight or to flee, muscles throughout our entire body are tensed in specific patterns of high energy readiness. When we are unable to complete the appropriate actions, we fail to discharge the tremendous energy generated by our survival preparations. This energy becomes fixed in specific patterns of neuromuscular readiness. The person then stays in a state of acute and then chronic arousal and dysfunction in the central nervous system.

It's not only the body where "energy becomes fixed in specific patterns," but the mind as well.

Human development is natural, there's an energy behind it that wants to expend itself, that wants to be discharged by the exertion that leads to real growth. In other words, moving from adolescence to adulthood is a basic human right, and in the grand scope of things, a pretty conventional fulfillment of basic natural processes.

But in the same way that basic natural processes like "feel threatened → prepare to fight or flee" can get interrupted and frozen into a psycho-physical cyst — so too can a basic natural process like "leave your old identity behind, encounter the inadequacy of your previous way of being, emerge as an adult psyche" get interrupted and leave some part of you frozen in amber, making superhero movie after superhero movie to fill the time between Star Wars movies and TV shows about teens and tweens who find out they have special powers.

The Broken Lock

If we accept this as a useful frame, that the Hero's Journey is an enactment of a transition from adolescence to adulthood, and further entertain the frame that the compulsive re-enactment of the Hero's Journey is indicative of that transition's failure to complete, then the next question becomes "how and why does this transition so consistently fail to complete in most individuals?"

On a mythic & structural level, I can pinpoint the point of failure pretty directly: we aren't dying.

In The Writer's Journey (one of the more famous books on storytelling with the Hero's Journey as a template) the author states it clearly:

Heroes must die so that they can be reborn... Heroes don't just visit death and come home. They return changed, transformed. No one can go through an experience at the edge of death without being changed in some way.

Both in our storytelling and our personal stories, this is the point where the key stops turning, where the lock gets stuck.

First, in our storytelling: the hero's "near-death" has become almost a running gag in the movies that fall into theaters year after year. The hero falls off the edge of the roof, the camera waits just a few beats too long to follow, aaaand then finally shows us that they've miraculously gripped the side and are pulling themselves up. Or the hero sinks underwater, and the camera lingers just a few beats too long before the hand breaks once more through the surface.

The problem isn't that the audience doesn't buy the hero’s demise. The problem is that the audience has no opportunity to participate in the psychic experience of the hero's death; and to the extent that the purpose of myths like this is to prepare people for the similar patterns when they play out in our own lives, the problem is that the audience is given no opportunity to glimpse the possibility of their own failure and death.

Oddly enough, one of the better examples I can think of — a movie that did offer some kind of participation in death — is Toy Story 3. In the end, the main characters are sliding down the trash pile into the incinerator, struggling to climb free before they all burn; then, one by one, they stop struggling; they accept their fate; they reach out to one another, take each others’ hands, and all realize together: this is how we go.

Yeah, I cried. My buddy next to me cried. I heard someone in the back of the theater choke out a sob. For whatever reason, the scene worked. It invited all of us into the intermingled grief and acceptance of the moment. (And then the heroes were rescued by "the claaaawwww," because of course they were it's a kids movie for god's sake.)

In the transition from adolescence to adulthood (as well as in the fiction structured by that pattern) what really matters isn't the surface level appearance. The letter of the law is a shadow here. It's only the underlying experience that matters, only the deeper currents of embodied participation that discharge the energy and bring transformation. Something in you has to struggle, fail, and die. It's not for nothing that Plotkin calls Late Adolescence "The Wanderer in the Cocoon."

Cut [a cocoon] open, and you will find a rotting caterpillar. What you will never find is that mythical creature, half caterpillar, half butterfly... No, the process of transformation consists almost entirely of decay.” (Pat Barker, quoted in A Field Guide to Getting Lost, by Rebecca Solnit)

This process of struggling, failing, and dying is hardly possible — at least not at scale — in a culture where our years of torrential, energetic outpouring-towards-growth are spent cooped up indoors, bound to a desk, judged from all directions by peers, parents, and authorities, not feeling like we're making contributions to the wider life of our family and society, forced to study subject after subject that we can clearly see no one cares about. There's no fruitful decay there, only sapped atrophy.

When this is the situation our "Heroic" impulses are met with week after week, year after year, we're never given a chance to come crying and striving face to face with the inadequacy of our efforts.

We are not given adequate chances to feel our failure to the marrow; to sink into the deeper currents of grief and let go of what we must now admit was a deficient way of being.

And so, we get taller without growing up. We itch at the Hero's Journey like long-lost twins fidgeting at their separate halves of a broken locket. We go to the theaters and the bookstores for one more turn on the Hero's Merry-Go-Round, one more spin where we can feel the key turn and turn, but never quite unlock the door.

And after a while, the turning becomes the point. Round and around, to escape your worries for a few moments. Any sense that the spinning was for something is lost. Anyone who suggests it had a purpose is a romantic, a naif, an atavism of some time when myth meant more than exploitable IP — which is to say, a dark age best left to the mists of time.

Completing the Journey (to continue the journey)

Of course, there's a difference between a culture and the individuals in a culture. It's a sticky subject. It's always possible for individuals to make it through the journey, to move into psychospiritual adulthood.

But when they arrive there, then what? They find themselves surrounded by a world-culture that has very little place or patience for them. Luckily, an adult is much better suited to deal with this reality than an adolescent is, but still — it's not easy for anyone. There's always that most human of longings: the longing for company.

I've seen hopes — and even some signs — that more and more people are re-discovering ways to complete the Hero's Journey, and that for many people who do, the first task they set themselves is to bring more people along with them. A generation of adult-midwives, helping to get more foot traffic over the threshold after a long lull.

I'm as hopeful as anyone, but I'm keeping my eyes on the canaries — one of the biggest, for me, is the prevalence of the Hero's Journey everywhere from movie theaters to writers workshops to inner work retreats to stoned conversations about economic history. When society stops re-enacting the pattern in every medium at every chance, I'll take that as a sign that the underlying frozen energy has been dissipated.

Until then, I wonder: What myths might we find to re-frame and re-fresh this journey, so people can approach it without all the baggage and false familiarity? And if the adventure is successful – what new myths might re-emerge to take its place?

Once we’ve opened the jammed door to true developmental adulthood, what grown-up myths will take on renewed importance?

Your recent posts have been absurdly salient to where I'm at right now. Regardless of whether this continues or diverges, please keep going!

On the topic of this post, I would love to know if you can point to any sources on other story structures beyond the hero's journey. Particularly any connected to early adulthood, by these definitions. I was trying to find material on alternative structures a few months ago, but most of what I could find was thinly disguised versions of the hero's journey.

This might be the most important essay I've read in 2024 so far.

I think it perfectly explains several things I find annoying about Western culture at the moment, and why adulthood itself has become pathologized in the Millennial/Gen Z sense of humor, and why so few people genuinely seem like adults now. And you explain it in a way that makes me realize they're all the same problem.

Kudos to you, this is a great essay.