What Does 'Imaginal' Mean?

Corbin, Dune, Sparkling Imagination, and Larvae

Heraclitus said we can’t step in the same river twice, for we are not the same person and it is not the same river.

I say that we cannot speak of the imaginal twice—for we are not the same person, and the word “imaginal” is a bugfuck free-for-all that never means the same thing twice.

“Imaginal” is kind of like “god” or “meditation” or “shadow,” in that way—it’s a word that’s used a lot in certain circles, but no one really pins down what they mean by it. They use it to evoke an area of stuff so you can locate their general vibe.

Okay, I’ll stop using the third person here: We. We never pin down what we mean by it.

I’m not going to use this space to pin down a meaning for “Imaginal,” if that’s even possible. I’m going to give a quick survey of it’s sturdiest and most common meanings, and then hopefully point towards what I mean when I say it.

Let’s start at the beginning, with the heavy stuff.

Corbin’s Imaginal

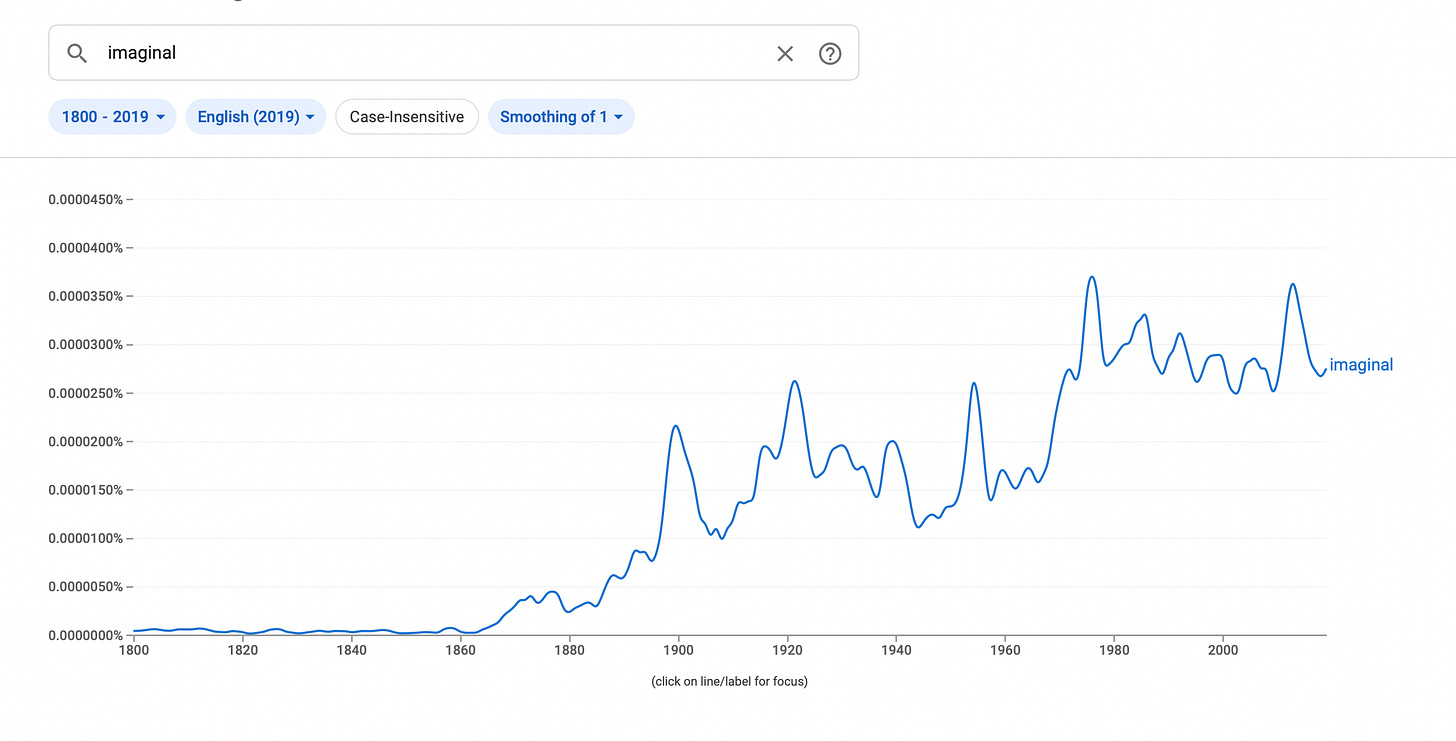

Take a look at the usage of the word “imaginal” in English. It wasn’t quite zero before 1860, but it was rare.

Most of the usage before the 1900s came from entomology,1 where imaginal is an adjective meaning “pertaining to the imago.” Helpful! The imago, in entomology, is the final form of an insect. Not immediately relevant, so we’ll skip it for now.

The usual story of the word imaginal, as we use it today, tends to go something like this: Henry Corbin, a French Scholar of Islamic Mysticism and close friend of Carl Jung2, brought to the attention of western academia the role of creative imagination in sufism, and separated this concept from our usual idea of "imagination" by introducing the term "imaginal" to French, which we then adopted into English when his work was translated.3

Corbin was an expert in more fields and more languages than most of us could claim to be amateurs in, and by all accounts he was something of an ideal of the Mystic-Scholar archetype. I mention this to explain why I’m going to skip any attempt to explain the cosmology behind his use of imaginal, because we’d be here all day, chasing up Islamic history and philology and depth psychology.

Instead, I’ll explain Corbin using Dune.

One of the terms Corbin lifted from the sufis and translated as imaginal was the idea of the alam al-mithal. This same term shows up exactly one time in Dune, where Frank Herbert lifted it from the same sources:

I dream, Paul reassured himself. It’s the spice meal.

Still, there was about him a feeling of abandonment. He wondered if it might be possible that his ruh-spirit had slipped over somehow into the world where the Fremen believed he had his true existence—into the alam al-mithal, the world of similitudes, that metaphysical realm where all physical limitations were removed. And he knew fear at the thought of such a place, because removal of all limitations meant removal of all points of reference. In the landscape of a myth he could not orient himself and say: “I am I because I am here.”

You can see the outline of it there, “the world where he had his true existence,” “the landscape of myth.” The alam al-mithal, and thus, the imaginal, is non-physical world that is, in many ways, more real than our world. The Fremen’s savior is seen not as a person in this world, but as a figure who’s True Existence is in some mythic landscape, and who’s presence here, in this world, is just one extension of that True Existence.

It’s important to understand that this is not a metaphor, or a distant legend, or (god forbid) a “psychotechnology.” As Tom Cheetham says, “This is no toy cosmology.” The imaginal is understood—by the sufis, by Corbin, and presumably by the Fremen—as a real, ontologically existent world, and one to which we have access.

This access comes from, you guessed it, the imagination—but only specific kinds of imagination. “The imagination can be innocuous,” Corbin says, “but the imaginal never can.” Here is where modern people have a hard time following, trained as we are to think of imagination as exclusively a personal faculty, used mostly for daydreaming, brainstorming, or making art. We don’t really grow up with the idea that—the same way you can either use your eyes to watch cartoon characters kill each other, or to gaze out at a mountain range, looking for your wife’s return home—you can use the imagination either to daydream about having lots of money and women, or to perceive the imaginal realm and the ways it forms the world around you.

That’s the over-shortened & over-simplified of the original meaning of imaginal. It is a world between our material world and the ineffable world of the divine, an intermediary world where divine will is shaped into mythic figures, places, and events, and where those mythic figures shine into our material world, to be acted out all around us. Our world is the theophany of the divine, and the imaginal realm is the channel through which the divine pours its will into us.

It’s Only Imaginal if It’s from the Corbin Region of Alam Al-Mithal…

Otherwise it’s just sparkling imagination.

There’s no point going through every other use of imaginal, point by point, it will suffice to give a few examples, and to note that if Corbin’s understanding of Sufi doctrine is the wellspring of our ideas of the imaginal, then we can track the rest of the uses by noticing how far they flow away from him, and by which routes.

Let’s simply check in with a few of the modern usages I see, scanning through Twitter, YouTube, and Amazon:

Imaginal Exposure

This term is a heavily medicalized usage, and is entirely separated from Corbin’s ideas of a world of mythic resonance that mediates the will of the divine.

“Imaginal Exposure” is a technique whereby traumatized people invoke their trauma through visualization, through calling up the sense-experience of the traumatic event. This is one step in the process of diminishing the effect of the trauma on their lives and their minds.

The only common note here is that it involves imagination, though it doesn’t view that imagination as substantively different from our capacity to daydream.

Imaginal Politics

This is the title of a book by Chiara Bottici, the jacket blurb for which defines the imaginal thusly:

Between the radical, creative capacity of our imagination and the social imaginary we are immersed in is an intermediate space philosophers have termed the imaginal, populated by images or (re)presentations that are presences in themselves.

We can see that, just like in Corbin, the imaginal is an intermediary space. But unlike Corbin, Bottici seems to view the imaginal capacity as little different from our capacity to daydream—just a souped-up social version of it.

Mysterious Realities…

With this book by Robert Moss (subtitled “A Dream Traveler’s Tales from the Imaginal Realm”), we venture into more ambiguous territory.

In the short space of the book’s jacket description, we get this spread of vocabulary: “The Unconscious,” “the imaginal realm, a higher reality that exists at the intersection of time and eternity,” “direct experience in the many worlds,” “the astral realm of Luna,” “the doors to the otherworld open from wherever you are,” “live on a mythic edge,” “lap of a goddess,” and “jaws of an archetype.”

At first glance, this might look aligned with Corbin—”at the intersection of time and eternity” doesn’t sound too different from “intermediary world between the divine and the material.” But it’s a pretty significant expansion and conflation—the Imaginal has escaped its specific place in a specific cosmology, and is now swallowing other domains, from the psychological (Unconscious, archetype) to the shamanic (many worlds, astral, doors to the otherworld) to the religious (goddess).

This might seem like a simple recognition of the similarities across different domains, how they seem to point to the same material, but it feels important to tag this conception of the Imaginal as a significant uptick in ambiguity and imaginal sprawl. Whether that’s a bad thing or not, I’m not convinced one way or the other, but we should note that it’s happening.

Imaginal Exercises

Unlike the above, this is not a specific technique or title, but a more general category. If you run in meditation, yoga, or inner work circles, you’ve probably participated in or been introduced to some type of exercise that called on the imagination or visualization.

These are pretty tricky to place, since any exercise can be approached from a number of angles.

For example, in my (archived) imaginal workshop, A Forest of Doorways, I had participants do an exercise called “The Lake.” The short version is—in the mind’s eye, we go to a quiet, secluded lake. We know that there is something important here in this scene. We hold the scene in our imagination, sense into it, move through it—and wait for the important hidden thing to show.

On the one hand, we could view this from a purely materialist psychological point of view: we’re providing our minds with a vessel into which it can drop a meaningful symbol.

On the other hand, we could view it from an imaginal point of view, in Corbin’s sense: we aim ourselves at the symbolic, mythic realm of the alam al-mithal, using a meaningful image as our north start to guide us to a region where hidden truths await us. We patiently stay there, allowing the True Existence of its form to approach us. We gain insight into the symbolic situation that is acting itself out in the material realm of our life.

And then there’s the attitude most people take in with them: ambivalence. On the one hand, they may want to believe the imaginal point of view—but it feels a little silly or dramatic, it doesn’t fit with the modern view of the world they carry. So they still do the exercise, holding onto the imaginal view loosely, aspirationally, but actually holding the ground-floor view that this is essentially a psychological exercise.

I’m not here to say anything positive or negative about one view or the other. I simply think it’s important to note that the word imaginal gets used for these exercises, regardless of the cosmology someone holds while carrying them out.

Where Does That Leave Us?

We are saying imaginal again, but we are not the same person and it is not the same word.

If you’re looking for a crib sheet to sum up what this word usually means you could do worse than:

Involving the imagination

Usually implying something not-just-in-your-head

Flavored with soul, intention, and/or spirituality.

Additionally, when me and people like me use the word, we’re talking about a particular zone of consciousness where experience comes alive, where deep truths and insights make themselves available to be seen and interacted with, where the unseen forces of this world allow you to approach them. It’s a place where your Mission in this world is waiting for you to notice and embody it.

I hope you found something helpful here; if you want to support my work and/or see more of it, see my Somatic Resonance course, Patreon, and link tree. Or just sign up for my Substack while you’re here.

I’ll also be starting a writing space soon, based around cultivating authentic expression, imaginal resonance, and true voice in writing. Leave your contact info on the site if you’re interested.

“The study of bugs,” if you don’t have endogenous entry to the etymology of entomology.

I wish I could say more about this here, since it’s clearly relevant, but I’m trying for a quick scan of the landscape here, so that can wait for another time.

I’ve seen this version of events a few times, and I don’t think it’s true. Just for one thing, there’s a couple English sources using the term “imaginal” to refer to the imagination around 1911 and 1917 (Corbin was a child at the time), so the word was definitely around, and being used in at least the same neighborhood… But Corbin did provide an incredibly impressive framework around a very specific usage of imaginal, which is the most important part of what we’re looking at, so we’ll pretend the above story is more true than it is.